The Capital Constraint: Why UK Banks Struggle to Turn Strength into Growth

Context

Growth in UK GDP has been sluggish, and the need for more investment has seldom been more critical.

Banks in the UK (“firms”) could very well provide the much needed spark, but they aren’t able to do so because of regulatory constraints and their approach to risk.

This article explores where and how these factors limit banks’ ability to put their capital reserves to better use.

Introduction

Firms are required to hold regulatory capital to absorb losses. However, banks in the UK often feel that they are holding heightened levels of regulatory capital, which is stifling their potential for evolution and expansion.

They might be right. Based on data from 15 firms, it is clear that they are holding more than enough capital to cover their losses. Specifically:

On average for every £1 of lending, firms are required to lock away an additional £0.09 (or 9%) from the economy in the form of regulatory capital. For some firms, the quantum of regulatory capital that is locked away could be as high as £0.20 for every £1 lent (i.e. 20%) [See footnote 1].

This figure is largely unjustified, because the data also shows that for every £1 lent over the last 5 years, the same firms, on average, have lost only £0.007 (or 0.7%) over the same duration, or 0.14% annually [See footnote 2]. This means that firms are holding > 60x as much capital as they might have required to cover their annual losses.

When the capital requirements of the UK’s larger banks are compared with equivalents in the USA and EU, the primary points of differentiation include the relatively higher levels of Countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) and Pillar 2A requirements in the UK. This inevitably requires the UK capital requirements to be higher than peer jurisdictions.

The common equity tier 1 [See footnote 3] (CET 1) capital requirement for non-systemic banks (non-GSIBs) stands at 8.8% in the US [See footnote 4]. In comparison, the minimum CET 1 capital requirement for similar banks in the UK is much higher – with the starting position itself being 9%, and additional CET 1 requirements in the form of firm-specific PRA buffers and Pillar 2 requirements are added on. This leads to some firms trying to comply with a CET 1 requirement of over 11%, sizably more than requirements in the US. Thus, there is a significant difference between the end-state CET 1 capital requirements that small and medium-sized banks in the UK are required to hold, relative to the US.

Whilst we acknowledge that capital requirements are designed to absorb the impact of severe stresses, one could argue that the gap between annual actual losses (0.14%) and capital requirements (9%) of 64x is materially high.

1) CCyB is too high

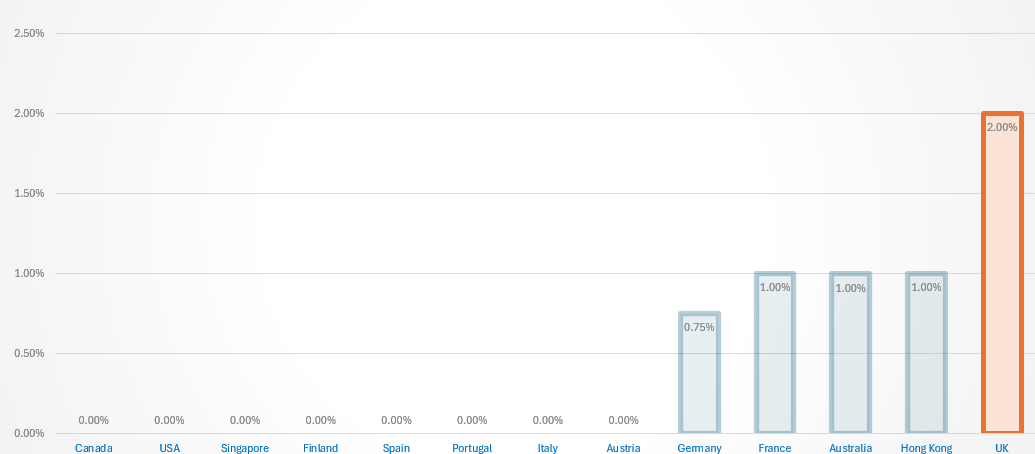

The current Counter-cyclical capital buffer (CCyB) rate of 2% is high in comparison to peer jurisdictions

CCyB is a tool that is used by the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) to make the banking system more resilient to cyclical risks. The CCyB rate in the UK oscillates between 0% and 2% (but could go as high as 2.5%), depending on the interplay between credit levels (i.e., lending) and the country’s GDP. In essence, during a period of growth the application of CCyB of up to 2% enables banks to absorb higher levels of credit risk losses that could arise due to greater lending activity. Conversely, where there is a shortage in lending (e.g., during a period of an economic shock or crisis), the CCyB is released allowing banks to lend more to support economic growth.

The CCyB rate in the UK is currently 2%, which is higher than most peers. In fact, the UK is one of only 17 countries that have implemented a positive neutral rate for the CCyB, and one of only four such countries to set it at 2%.

It is important to note that paragraph 30.7 of the Basel Framework [See footnote 5] says that the focus on excess aggregate credit growth means that jurisdictions are likely to only need to deploy the buffer on an infrequent basis. This suggests that the original Basel design of the CCyB did not envisage jurisdictions having consistently high positive neutral rates, such as the 2% rate in the UK. Therefore, the current operation of the CCyB in the UK seems to have deviated from the BCBS’s original design, which might result in UK banks holding higher levels of capital than those of comparable nations.

For instance, Canada, USA, Singapore, Finland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Austria have all set their current CCyB rate at 0%. Further, Germany’s rate is currently 0.75%, while France, Australia, and Hong Kong have set their rate at 1%. This puts the UK in a potentially disadvantageous position, despite the minimal CCyB offset that is granted to some firms. This leads to firms in the UK requiring to hold more capital for CCyB than they would need to in other jurisdictions. This deprives the economy from greater availability of funds for economic growth.

CCyB across jurisdictions

In practice, the cyclical nature of the CCyB deters boards from releasing capital after rates drop, in anticipation of subsequent increases

As mentioned before, the CCyB is cyclical in nature, and is set between 0% and 2% depending on the gap between credit (lending) and GDP. During periods of economic slowdown when lending drops, CCyB is also reduced. In time, when trading conditions improve, the PRA exercises the right to increase the CCyB, requiring banks to cope with the raised capital requirements over a 12-month period, or less during exceptional circumstances.

Banks are therefore wary of releasing capital that is made available when the PRA lowers the CCyB, due to the expectation of needing to quickly comply with subsequent increases. As such, although the PRA could argue that from an entirely theoretical perspective, its approach to lowering CCyB allows firms to put more of their capital resources – which are otherwise locked away – to good use, this is not reflected in practice. This issue is exacerbated when banks aim to generate the higher CET1 capital requirement organically – which could be constraining – for example, due to their ownership structure, or through accumulation of earnings which can only be counted after they have been audited.

2) D-SIBs may hold more capital than G-SIBs

Domestic systemic firms can sometimes be required to hold more regulatory capital than Global systemic firms

Systemic firms – both domestic and global – are rightly required to hold more capital than smaller firms. This is because their instability would have more impact on the economy than their smaller counterparts.

The additional requirement for domestic systemic firms can range from 0% to 3% of their risk-weighted assets, while the same for global systemic firms could be between 1% and 3.5%. That said, conceptually, systemic risks arising from domestic firms is often less than systemic risks from a global firm. As such, the corresponding regulatory capital requirement for the former should generally be less than the latter. But, the overlap of 2% allows makes it highly probable for the current regulatory requirements leave room for exactly that.

3) UK geographic concentration Pillar 2 add-on

The geographical concentration risk impact on firms that lend primarily to UK companies is high, and disincentivises UK lending

Firms are rightly required to hold additional capital to mitigate the risk of concentration in their lending. However, applying this requirement for lending in the UK discourages firms from making funds available to fuel the country’s economic growth.

Firms that lend primarily in the UK, and therefore support growth in the country’s domestic sector, are required to hold additional regulatory capital to reflect the UK concentration risk. For some firms, this additional capital requirement amounts to as much as 70% of their Pillar 2A capital requirements in addition to any UK specific CCyB. This makes certain retail products and lending to UK companies more capital intensive and inadvertently encourages firms to focus some amount of lending on other jurisdictions even when the UK is their primary base and key area of credit expertise.

Firms that have non-UK books are typically subject to lower effective CCyB, as it is derived from the pass through rate from the jurisdictions where the exposure are located. Firms that reduce the size of their foreign exposures in favour of the UK will therefore not only need to hold more regulatory capital due to an increase in their effective CCyB, but also due to increases in UK concentration. This further disincentivises firms from lending in the UK.

4) Regulatory messaging on the usability of capital buffers

Firms are reluctant to unlock their capital buffers during periods of economic slowdown, despite being allowed to do so, due to their fear of PRA’s response to firms’ usage of buffers

The PRA has always been clear that firms can, and should, use their buffers to unlock capital resources during periods of economic and idiosyncratic stress. Despite this, firms seldom dip into their buffers during such periods, meaning that capital resources are unnecessarily locked away from being introduced into the economy to promote growth. Why could this be?

Firms say that this is driven by the lack clarity about how the PRA will react if they do dip into their buffers during stress, and most are wary of being subject to expensive skilled person reviews and over-intrusive supervisory scrutiny. For example, clarifying that ICAAP stress testing should be done against TCR only, and/or being clear about how the PRA’s supervision would change for firms that have dipped into their buffers during stress, may encourage firms to treat their buffers more flexibly than they do today.

Firms are cautious about the possibility of regulatory interventions interfering with their ability to focus on doing business, especially during periods of stress. As such, they often plan to avoid dipping into their buffers altogether. This in turn leads to firms holding more capital than they need to, thereby maintaining a “buffer on buffer” to absorb the impact of stress, and therefore operating a “buffer on buffer on buffer” during business-as-usual. Such practices deprive the economy from higher levels of funding, limiting growth.

5) Outdated and conservative thresholds

Various PRA thresholds do not account for inflationary impacts since they were last set, meaning that more firms are subject to “prudential drag”, meaning that regulatory requirements become disproportionate to the intentions they serve

The PRA rulebook and the UK CRR contains several thresholds passing which would require firms to comply with greater regulatory burden. Some of these thresholds have been in place from before the global financial crisis. As such, the application of the same thresholds in the present day, without being indexed in line with inflation, is not fit-for-purpose. This results in ‘prudential drag’ whereby thresholds that are set in nominal terms ‘tighten’ as inflation and other factors increase the nominal size of the economy – and so the threshold captures a different set of firms than originally intended.

A non-exhaustive list of such thresholds that will benefit from indexation is below.

CRR Article 123 provides a €1m threshold for the application of the 75% risk weight to the retail exposure class. The PRA is translating this to £880k under its implementation of Basel 3.1. The €1m has applied since at least 2013.

CRR Article 208 requires that for loans exceeding €3m the property valuation be reviewed every 3 years. The PRA is translating the €3m to £2.6m under Basel 3.1. The €3m has applied since at least 2013.

CRR Article 395 imposes a limit of €150m for a group of connected counterparties, which the PRA has translated to £130m in the PRA rulebook. The €150m threshold has been in place since at least 2013.

There are a number of liquidity reporting thresholds that haven’t been updated since they first came into place. For instance:

The retail deposit threshold of €1m (CRR Article 411) has been translated to £880k in the PRA rulebook. A similar translation also applies to the SME turnover limit.

Similarly, limits around collective investment units (CIUs) of €500m (CRR Article 416) has been translated to £440m in the PRA rulebook.

CRR Article 450 defines a high earner as those earning €1m per annum or more, which the PRA rulebook has retained. This threshold has been in place since 2013.

The Regulatory Reporting Part of the PRA Rulebook includes proportionality for FINREP reporting, meaning that firms with total assets less than £5 billion are only required to submit a smaller number of returns. This £5 billion has applied since 2018.

CRR Article 94 sets the small trading book threshold at €50m which has been translated to £44m in the PRA rulebook. The €50m threshold has been in place from early 2021.

Conclusion

As such, it is a combination of regulatory pressures and firm-specific idiosyncrasies that contribute to excessive capital being locked away. Off-late, the regulator has acknowledged a lot of such concerns and made changes to their policy making (e.g. greater use of indexation). However, a key question remains - could firms do more address their own approach towards striking a more optimum balance between holding regulatory capital and putting such funds to better use?

Footnotes

[1] This is based on firms’ data on their overall capital requirement and size of loan book as at last year end

[2] This is based on the same firms’ cumulative lending and historical losses over the last 5 years

[3] Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital is the highest quality of regulatory capital for financial institutions, primarily consisting of common shares, retained earnings, and certain reserves

[4] https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/large-bank-capital-requirements-20240828.pdf

[5] https://www.bis.org/baselframework/BaselFramework.pdf

For more information, please contact:

Anindya Ghosh Chowdhury, Chief Growth Officer

T: +44 (0)740 767 9600 E: anindya.gchowdhury@katalysys.com